Improving the tests for RestAssured.Net with mutation testing and Stryker.NET

This post was published on February 10, 2025When I build and release new features or bug fixes for RestAssured.Net, I rely heavily on the acceptance tests that I wrote over time. Next to serving as living documentation for the library, I run these tests both locally and on every push to GitHub to see if I didn’t accidentally break something, for different versions of .NET.

But how reliable are these tests really? Can I trust them to pass and fail when they should? Did I cover all the things that are important?

I speak, write and teach about the importance of testing your tests on a regular basis, so it makes sense to start walking the talk and get more insight into the quality of the RestAssured.Net test suite. One approach to learning more about the quality of your tests is through a technique called mutation testing.

I speak about and demo testing your tests and using mutation testing to do so on a regular basis (you can watch a recent talk here), but until now, I’ve pretty much exclusively used PITest for Java. As RestAssured.Net is a C# library, I can’t use PITest, but I’d heard many good things about Stryker.NET, so this would be a perfect opportunity to finally use it.

Adding Stryker.NET to the RestAssured.Net project

The first step was to add Stryker.Net to the RestAssured.Net project. Stryker.NET is a dotnet tool, so installing it is straightforward: run

dotnet new tool-manifest

to create a new, project-specific tool manifest (this was the first local dotnet tool for this project) and then

dotnet tool install dotnet-stryker

to add Stryker.NET as a dotnet tool to the project.

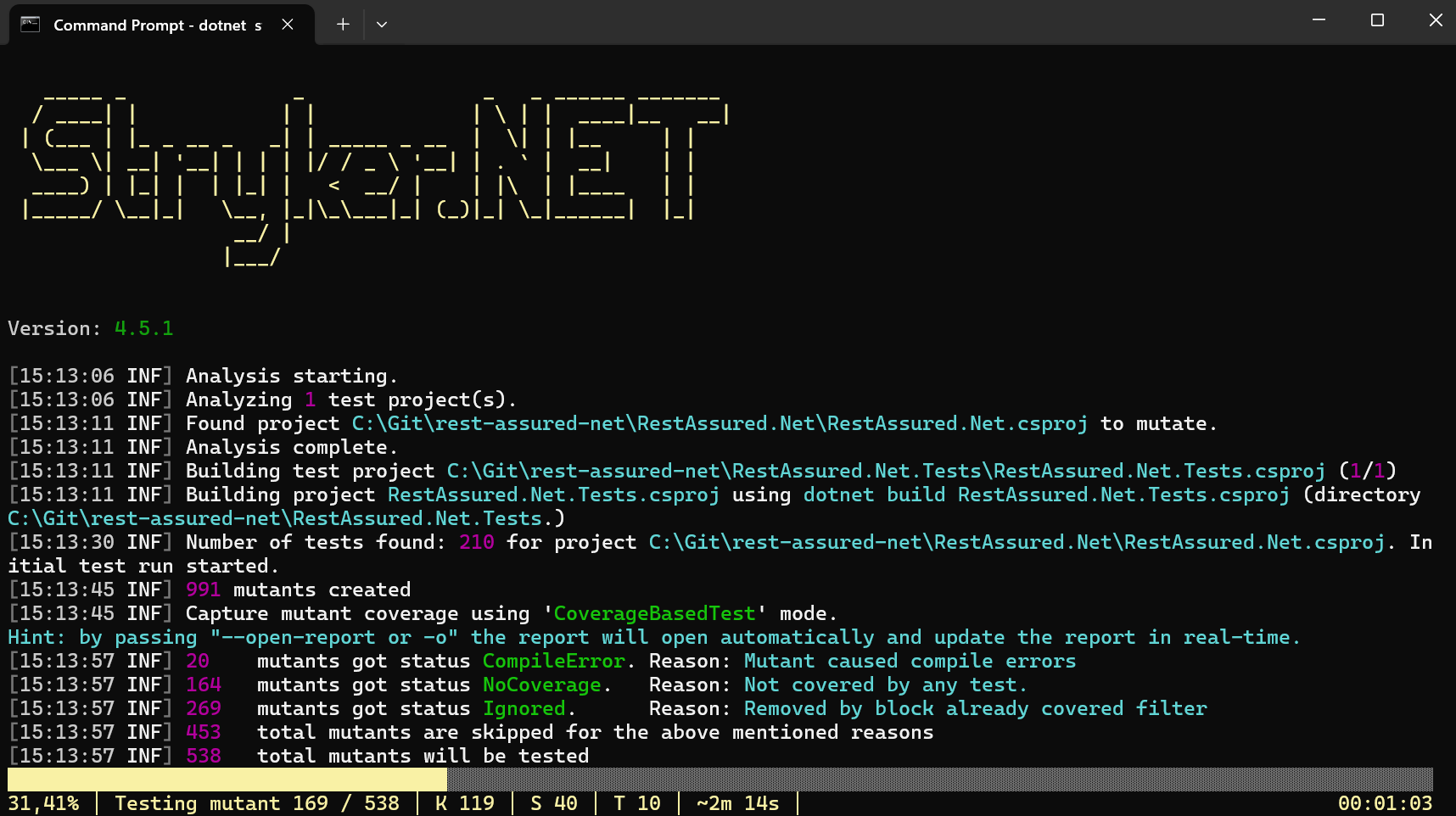

Running mutation tests for the first time

Running mutation tests with Stryker.NET is just as straightforward:

dotnet stryker --project RestAssured.Net.csproj

from the tests project folder is all it takes.

Because both my test suite (about 200 tests) and the project itself are relatively small code bases, and because my test suite runs quickly, running mutation tests for my entire project works for me. It still took around five minutes for the process to complete. If you have a larger code base, and longer-running test suites, you’ll see that mutation testing will take much, much longer.

In that case, it’s probably best to start on a subset of your code base and a subset of your test suite.

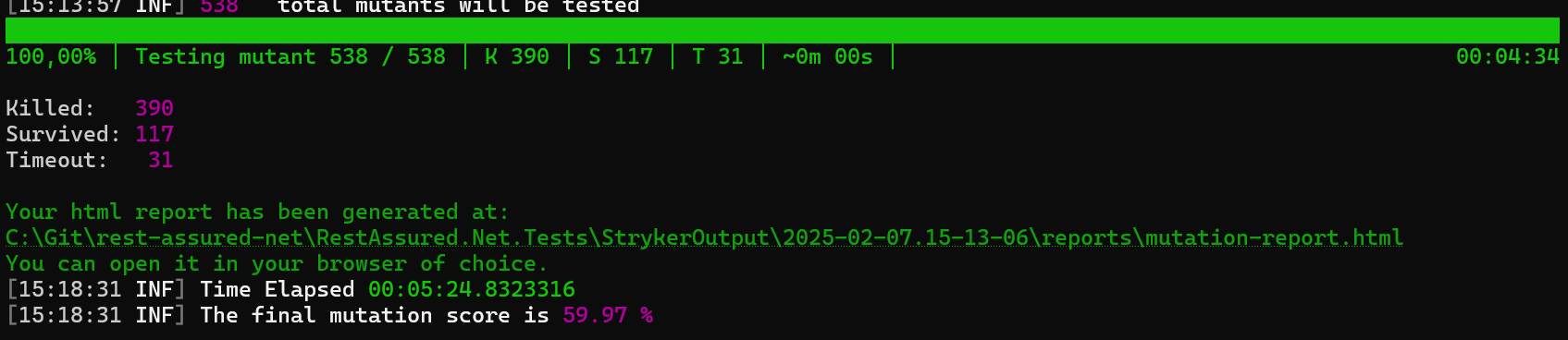

After five minutes and change, the results are in: Stryker.NET created 538 mutants from my application code base.

Of these:

- 390 were killed, that is, at least one test failed because of this mutation,

- 117 survived, that is, the change did not make any of the tests fail, and

- 31 resulted in a timeout, which I’ll need to investigate further, but I suspect it has something to do with HTTP timeouts (RestAssured.Net is an HTTP API testing library, and all acceptance tests perform actual HTTP requests)

This leads to an overall mutation testing score of 59.97%.

Is that good? Is that bad?

In all honesty, I don’t know, and I don’t care. Just like with code coverage, I am not a fan of setting fixed targets for this type of metric, as these will typically lead to writing tests for the sake of improving a score rather than for actual improvement of the code. What I am much more interested in is the information that Stryker.NET produced during the mutation testing process.

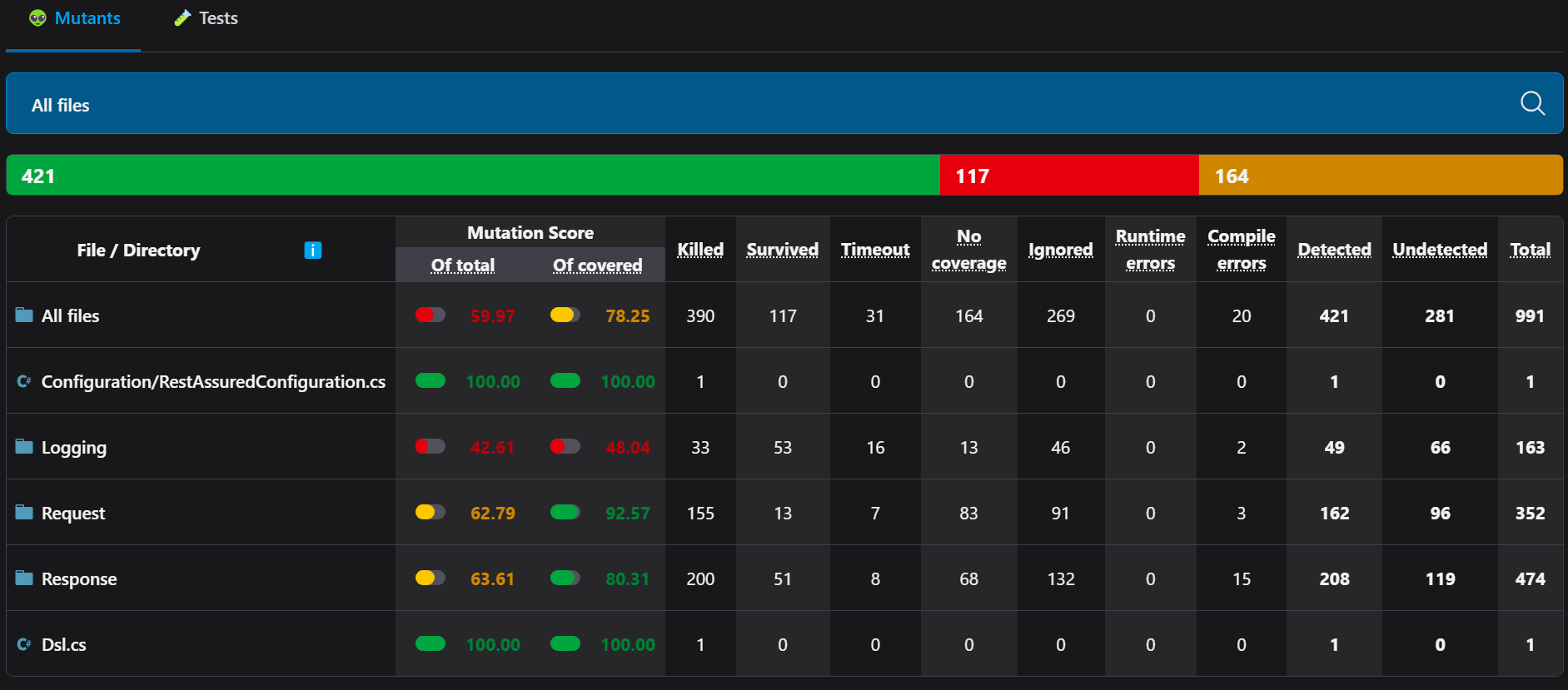

Opening the HTML report

I was surprised to see that out of the box, Stryker.NET produces a very good-looking and incredibly helpful HTML report. It provides both a high-level overview of the results:

as well as in-depth detail for every mutant that was killed or that survived. It offers a breakdown of the results per namespace and per class, and it is the starting point for further drilling down into results for individual mutants.

Let’s have a look and see if the report provides some useful, actionable information for us to improve the RestAssured.Net test suite.

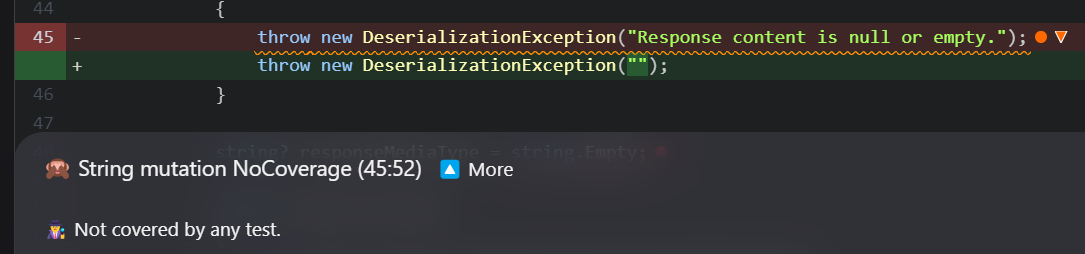

Missing coverage

Like many other mutation testing tools, Stryker.NET provides code coverage information along with mutation coverage information. That is, if there is code in the application code base that was mutated, but that is not covered by any of the tests, Stryker.NET will inform you about it.

Here’s an example:

Stryker.NET changed the message of an exception thrown when RestAssured.Net is asked to deserialize a response body that is either null or empty. Apparently, there is no test in the test suite that covers this path in the code. As this particular code path deals with exception handling, it’s probably a good idea to add a test for it:

[Test]

public void EmptyResponseBodyThrowsTheExpectedException()

{

var de = Assert.Throws<DeserializationException>(() =>

{

Location responseLocation = (Location)Given()

.When()

.Get($"{MOCK_SERVER_BASE_URL}/empty-response-body")

.DeserializeTo(typeof(Location));

});

Assert.That(de?.Message, Is.EqualTo("Response content is null or empty."));

}I added the corresponding test in this commit.

Removed code blocks

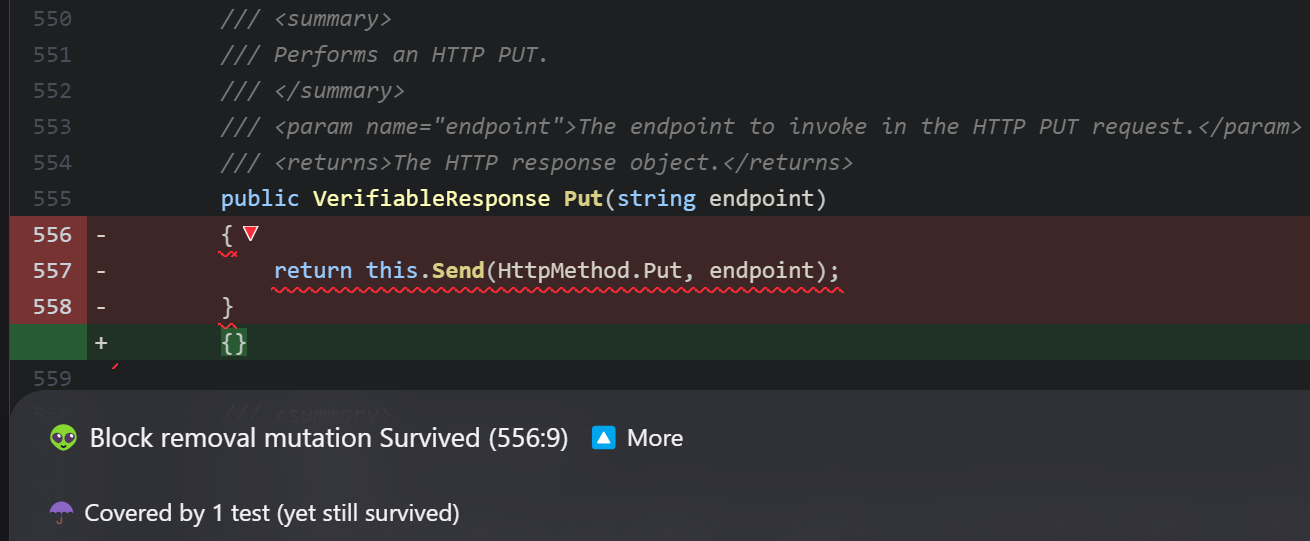

Another type of mutant that Stryker.NET generates is the removal of a code block. Going by the mutation testing report, it seems like there are a few of these mutants that are not detected by any of the tests. Here’s an example:

The return statement for the Put() method body, which is used to perform an HTTP PUT operation, is replaced with an empty method body, but this is not picked up by any of the tests. The same applies to the methods for HTTP PATCH, DELETE, HEAD and OPTIONS.

Looking at the tests that cover the different HTTP verbs, this makes sense. While I do call each of these HTTP methods in a test, I don’t assert on the result for the aforementioned HTTP verbs. I am basically relying on the fact that no exception is thrown when I call Put() when I say ‘it works’.

Let’s change that by at least asserting on a property of the response that is returned when these HTTP verbs are used:

[Test]

public void HttpPutCanBeUsed()

{

Given()

.When()

.Put($"{MOCK_SERVER_BASE_URL}/http-put")

.Then()

.StatusCode(200);

}These assertions were added to the RestAssured.Net test suite in this commit.

Improving testability

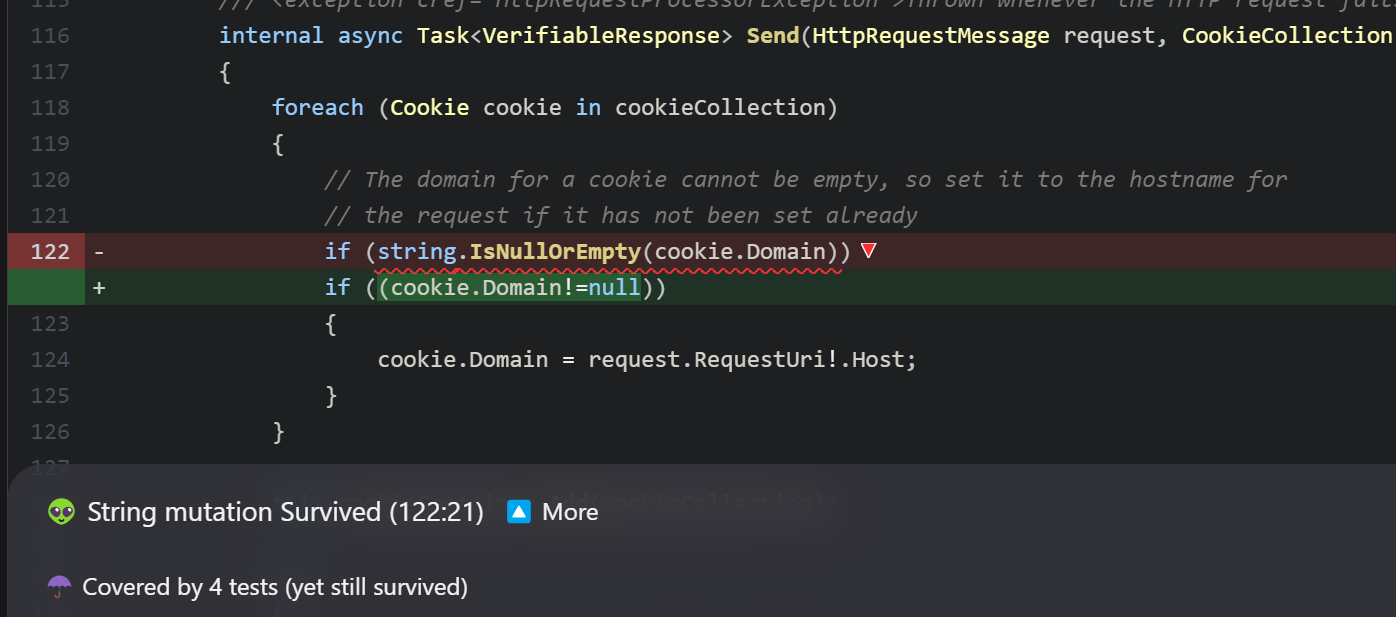

The next signal I received from this initial mutation testing run is an interesting one. It tells me that even though I have acceptance tests that add cookies to the request and that only pass when the request contains the cookies I set, I’m not properly covering some logic that I added:

To understand what is going on here, it is useful to know that a Cookie in C# offers a constructor that creates a Cookie specifying only a name and a value, but that a cookie has to have a domain value set. To enforce that, I added the logic you see in the screenshot. However, Stryker.NET tells me I’m not properly testing this logic, because changing its implementation doesn’t cause any tests to fail.

Now, I might be able to test this specific logic with a few added acceptance tests, but it really is only a small piece of logic, and I should be able to test that logic in isolation, right? Well, not with the code written in the way it currently is…

So, time to extract that piece of logic into a class of its own, which will improve both the modularity of the code and allow me to test it in isolation. First, let’s extract the logic into a CookieUtils class:

internal class CookieUtils

{

internal Cookie SetDomainFor(Cookie cookie, string hostname)

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(cookie.Domain))

{

cookie.Domain = hostname;

}

return cookie;

}

}I deliberately made this class internal as I don’t want it to be directly accessible to RestAssured.Net users. However, as I do need to access it in the tests, I have to add this little snippet to the RestAssured.Net.csproj file:

<ItemGroup>

<InternalsVisibleTo Include="$(MSBuildProjectName).Tests" />

</ItemGroup>Now, I can add unit tests that should cover both paths in the SetDomainFor() logic:

[Test]

public void CookieDomainIsSetToDefaultValueWhenNotSpecified()

{

Cookie cookie = new Cookie("cookie_name", "cookie_value");

CookieUtils cookieUtils = new CookieUtils();

cookie = cookieUtils.SetDomainFor(cookie, "localhost");

Assert.That(cookie.Domain, Is.EqualTo("localhost"));

}

[Test]

public void CookieDomainIsUnchangedWhenSpecifiedAlready()

{

Cookie cookie = new Cookie("cookie_name", "cookie_value", "/my_path", "strawberry.com");

CookieUtils cookieUtils = new CookieUtils();

cookie = cookieUtils.SetDomainFor(cookie, "localhost");

Assert.That(cookie.Domain, Is.EqualTo("strawberry.com"));

}These changes were added to the RestAssured.Net source and test code in this commit.

An interesting mutation

So far, all the signals that appeared in the mutation testing report generated by Stryker.NET have been valuable, as in: they have pointed me at code that isn’t covered by any tests yet, to tests that could be improved, and they have led to code refactoring to improve testability.

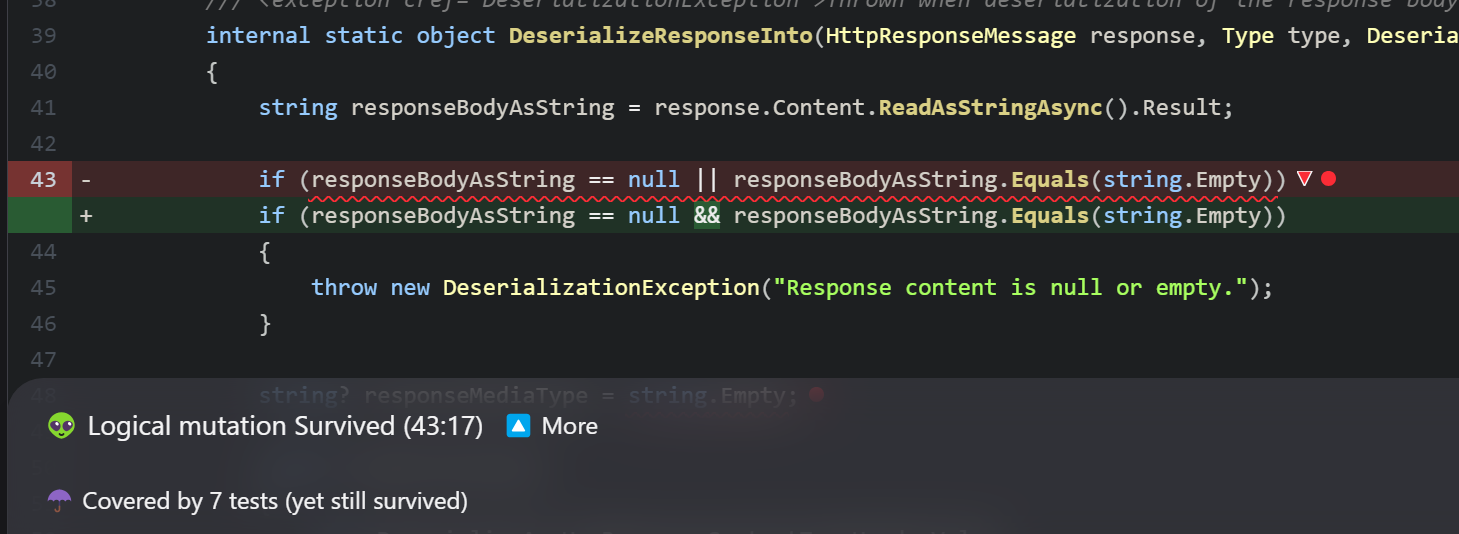

Using Stryker.NET (and mutation testing in general) does sometimes lead to some, well, interesting mutations, like this one:

I’m checking that a certain string is either null or an empty string, and if either condition is true, RestAssured.Net throws an exception. Perfectly valid. However, Stryker.NET changes the logical OR to a logical AND (a common mutation), which makes it impossible for the condition to evaluate to true.

Is that even a useful mutation to make? Well, to some extent, it is. Even if the code doesn’t make sense anymore after it has been mutated, it does tell you that your tests for this logical condition probably need some improvement. In this case, I don’t have to add more tests, as we discussed this exact statement earlier (remember that it had no test coverage at all).

It did make me look at this statement once again, though, and I only then realized that I could simplify this code snippet to

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(responseBodyAsString))

{

throw new DeserializationException("Response content is null or empty.");

}Instead of a custom-built logical OR, I am now using a construct built into C#, which is arguably the safer choice.

In general, if your mutation testing tool generates several (or even many) mutants for the same code statement or block, it might be a good idea to have another look at that code and see if it can be simplified. This was just a very small example, but I think this observation holds true in general.

This change was added to the RestAssured.Net source and test code in this commit.

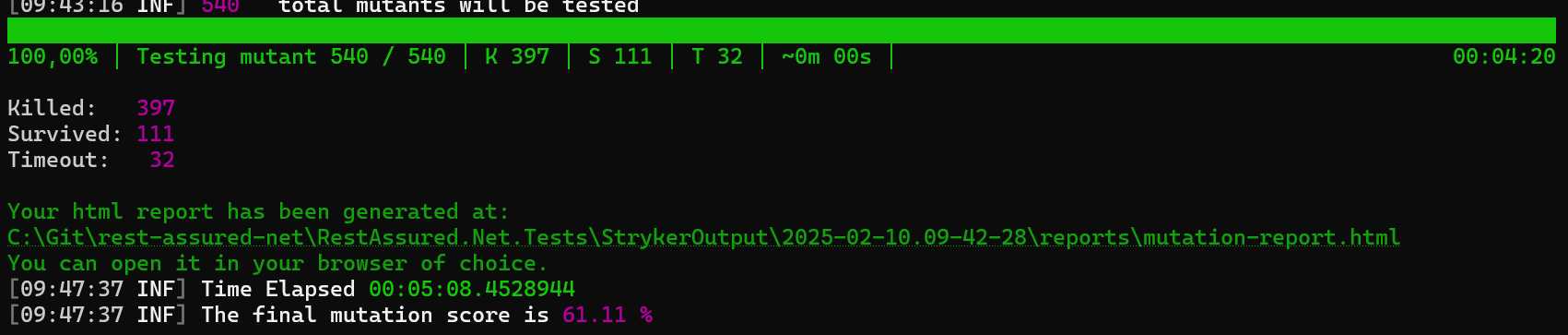

Running mutation tests again and inspecting the results

Now that several (supposed) improvements to the tests and the code have been made, let’s run the mutation tests another time to see if the changes improved our score.

In short:

- 397 mutants were killed now, up from 390 (that’s good)

- 111 mutants survived, down from 117 (that’s also good)

- there were 32 timeouts, up from 31 (that needs some further investigation)

A closer look at the HTML report generated for this new mutation testing run reveals that all the signals I discussed in this blog post have been successfully resolved. That’s progress.

Overall, the mutation testing score went up from 59,97% to 61,11%. This might not seem like much, but it is definitely a step in the right direction. The most important thing for me right now is that my tests for RestAssured.Net have improved, my code has improved and I learned a lot about mutation testing and Stryker.NET in the process.

Am I going to run mutation tests every time I make a change? Probably not. There is quite a lot of information to go through, and that takes time, time that I don’t want to spend for every build. For that reason, I’m also not going to make these mutation tests part of the build and test pipeline for RestAssured.Net, at least not any time soon.

This was nonetheless both a very valuable and a very enjoyable exercise, and I’ll definitely keep improving the tests and the code for RestAssured.Net using the suggestions that Stryker.NET presents.

"