The test automation quadrant, or a different way to look at your tests

This post was published on December 11, 2024Like many others working in software testing, and more specifically in automation, I have been introduced to the concept of the test automation pyramid early on in my career. While this model has received its share of criticism in the testing community over the years, I still use it from time to time.

What I think this model is still somewhat useful for is introducing people who are relatively new to software testing and automation to testing scopes, layers and, most importantly, to thinking and talking about finding the right balance between different test scopes. After all, they will encounter this model at some point in time, and I’d rather they learn about this model in context.

However, recently I have started to think and talk about classification of automated tests in a different way, using a different kind of mental model, and I thought it might be useful to share this model with you.

Please note that whenever I use the word ‘test’ in the remainder of this blog post, I’m referring to an automated test / check that confirms or falsifies an expectation about the behaviour of our product. I don’t think the model applies equally well to exploratory testing activities (but I’m happy to be proven wrong).

Why a different model?

Because I think that while the test automation pyramid still has its use in certain contexts, there are a couple of things about it that I feel are missing:

-

Regarding the layers and their boundaries: I sometimes joke that if I’d ask five developers for a definition of a unit test, I’d get at least six different answers. People and teams use different definitions of what a unit / integration / E2E test is, and where one stops and the next one begins. This tends to result in a lot of confusion and back-and-forth on what is (not) a unit test, for example, and I’d rather save my energy for more important conversations.

-

Regarding the model itself: what is completely missing in the pyramid model is a representation of the value of a test. I know, I know, it’s just a model, and all models are wrong, but there is so much talk about the amount of testing one should do in general, what part of that testing should be automated, what part of that automation should be at the unit / integration / E2E level and what is a good amount of line / branch / method / requirement coverage, yet so rarely do we talk about the value of our tests. I think we need a model that at least takes the value of a test into account.

-

Regarding how people talk about / use the model: as I said, there is a lot of talk about the shape of the model and what that says about the ratio of unit to integration to E2E tests. And you know what? I don’t particularly care. I don’t think it is interesting at all what your ratios look like, no matter if it is a pyramid (well, a triangle, really), an hourglass, an ice cream cone, or some other shape. It’s all good, as long as your tests are efficient and valuable. In other words, I think there are better ways to have a conversation about your tests and the value they provide, and we need a model that supports that.

So, then what?

My current mental model of (classification of) tests

Let’s take a quick step back first: why do we use automation? Why do we use tools to help us when we test? If you ask me, it’s because we want to retrieve and present valuable information about the state of our product and potential risks in a way that is efficient.

Following this, there are two factors that play a key role in test automation: information, specifically information that is valuable, and efficiency, or the amount of resources we need to spend to get the information that we’re looking for.

With these two things in mind, here’s what my mental model looks like these days when I talk about automated tests:

You could call this model a test automation quadrant. In its essence, it’s a very simple model, and yes, there are lots of nuances that are missing. That’s why it’s called a model. Now, let me clarify why this model looks the way it does and what my thought process behind it is.

On the horizontal axis, there’s information value. As testers, we are in the business of uncovering and presenting information, more specifically, information about the state of our product. Not all information is equal, though, with some pieces of information being more important than others. Tests that uncover and present valuable information are inherently more valuable themselves than tests that uncover and present less valuable information. Also, the value of information is undeniably related to risk. Information related to high-risk problems is more valuable than information related to low-risk problems.

By information, I mean the confirmation or falsification of assumptions, beliefs or expectations about the state or the behaviour of the product we’re building. Since we’re talking about automation here, most effort will focus on confirming pre-existing, codified expectations through assertions, but automation is not limited to executing assertions and demonstrating that something might work.

Oh, and the value of the information is not limited to the information itself and what it tells you about the state of your product, it also includes the reliability of that information. There’s no point in tests that tell you something is broken when you can’t trust that test.

On the vertical axis, we have efficiency. All other things being equal, tests that are more efficient are generally preferable over tests that are less efficient. As time typically equals money, efficiency includes the time to read, write, run and maintain a test, and also the time it takes to analyze the root cause in case of a failure. Besides time, we might also want to consider the cost of hard- and software required to write and run the test, as well as other things related to efficiency.

Please note that unlike the test automation pyramid, I’m leaving the scope or size of the test by itself out of the equation. E2E tests can be more efficient or less efficient, and the information produced by these tests can be more valuable or less valuable. The same applies to unit and integration tests. Oh, and the model applies to automated performance testing, security testing and other types of test automation, too. All of these can produce information that is more or is less valuable, and they can be done in a more or in a less efficient way.

So, now that you understand the reasoning behind this model and the aspects of tests considered in it, let’s take a look at how you can use this test automation quadrant to your benefit.

Use the test automation quadrant to assess your current situation

When you decide to use this model, the first step I recommend you take is to place your tests somewhere in one of these quadrants. Of course, the exact spot differs for different types of tests, and even for individual tests. That’s a perk of this model, if you’d ask me: you can apply it to your entire test suite, to separate types of tests and even to individual test cases.

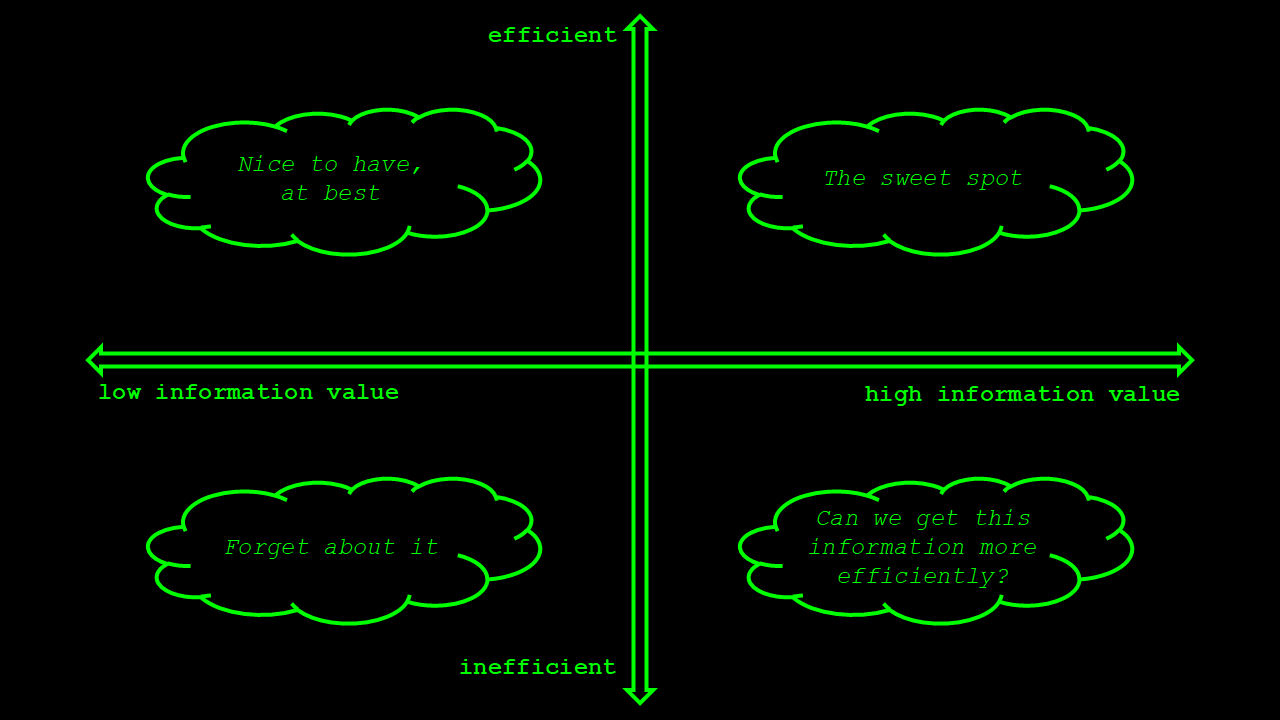

Ideally, most of your tests should find a place somewhere in the top right quadrant, i.e., these are efficient tests that provide valuable information. Will all your tests be in the top right quadrant? Probably not, but that doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing. Remember, we’re simply taking stock of our current situation for now.

Tests that are in the bottom right quadrant, for example, still produce high value information, just not in a very efficient way. Maybe the tests take a long time to write or to run. Maybe you need to do a significant amount of setup in dependent systems. Maybe there’s another reason your test isn’t as efficient as you would want it to be. Still, they produce valuable information, so it is probably in your best interest to keep them.

When we move to the left two quadrants, things get a little more tricky. Tests in the top left quadrant can be written and run efficiently, but the information they produce is not very valuable. I do not want to imply that you shouldn’t write these tests, but what I do recommend is to give them a (much) lower priority than those tests on the right hand side of the quadrant, and only work on these when you have the time and resources available to do so. Or, if you want to be a little more ruthless, consider not spending any time on them at all.

As for tests in the bottom left corner of the quadrant: I strongly recommend you to stop spending time on them. At all. Don’t write new tests that fall into this part of the quadrant, and strongly consider throwing away existing tests here. They likely cost you a lot of time and effort to write and run, and they don’t produce a lot of value in return.

Summarizing the above in a picture:

Use the test automation quadrant to improve your automation efforts

After you have assessed your current situation, for an individual test, a group of related tests or even for your entire test suite, the second step is to identify and carry out steps to bring some or all of your tests closer to the top right corner of the quadrant, either by moving them up, moving them to the right, or both.

Moving tests up implies making existing tests more efficient in a way that does not negatively impact the value of the information they provide. How to do this exactly is outside the scope of this blog post, and the exact steps to take heavily depend on context, but here are some suggestions for steps to take:

- Breaking down existing E2E tests into smaller, more focused tests that run more efficiently

- Refactoring application code that is hard to test by applying principles such as single responsibility and dependency inversion

- Using a simulated version of a third-party dependency instead of ‘the real thing’ for cases that are hard or even impossible to set up

Moving tests to the right implies improving tests that produce low value information or information that is not reliable. Here are some examples of actions you may consider taking to achieve this:

- Gather data from flaky tests, try and find the root cause of their flakiness and address issues

- Test your tests, for example using techniques like mutation testing, to identify potential false negatives and improve the effectiveness of your test suite, for example around boundary values

- Improve the reporting of your test suite to make it more clear what exactly happened in case of failing tests

Again, this is a very generic list of suggestions, and one that is far from complete. In a follow-up blog post, I’ll go through different realistic examples and show you how to apply these techniques on actual tests to move them further up and / or to the right in the test automation quadrant.

This blog post is just a first introduction to the test automation quadrant model, and there is much more to unpack here yet. Still, I’m very much looking forward to your feedback and comments.

In the meantime, I’m not just working on a post with actual examples, but also on a brand-new talk on this model that I am looking to deliver at events, meetups and conferences in 2025. Maybe at your event, too?

"